CxD #177: 🏀 ☄️

1.

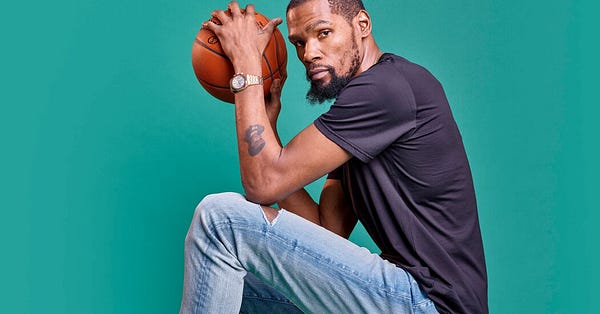

This article (which also has an audio version for you podcast listeners) about Kevin Durant and the team that will win this year’s NBA championship, is one of the most excellent examples of a writer doing things with words that others just can’t. I won’t go on about the craft of writing itself, but consider how you might have tried to write about the unusual character of one of the world’s most famous athletes, and compare those efforts with how this journalist does it:

Ok, why not, let’s start with the asteroid. Thirty-five million years ago, a giant space rock, two miles wide, came screaming out of the sky and crashed into Earth. It struck the eastern edge of the landmass we know today as North America. And it unleashed an apocalypse. The asteroid hit with the power of many nuclear bombs. It hit so hard that it vaporized itself and cracked the bedrock seven miles down. It incinerated whole forests, killed all life in the area, sent super-tsunamis ripping out across the Atlantic. You can still find remnants of the trauma (shocked quartz, fused glass) as far away as Texas and the Caribbean.

For those of you who are anti-clicking on any links, here’s some choice sections about Character:

She knew that Kevin was sensitive but also that he couldn’t afford to be soft. So she had a rule. He was allowed to cry but not to whine. If you get hurt, Wanda taught him, you should express that pain, no matter what anybody else says. Crying is natural. It is the truth. But whining is something else — a manipulation, an attempt to extend your pain to get something you didn’t earn.

Durant looks, especially, at Twitter. N.B.A. Twitter is a whole vibrant world unto itself, an extension and amplifier of all the on-court drama, and in that world K.D. is a sort of trickster god. He has almost 19 million followers and is famous for responding to his critics, whether they are journalists or talking heads or fellow players or random kids. “ok you’re right bro,” he once wrote to someone who called him a coward. “We got that out of the way. I feel u, I hear you loud and clear. You good now??”

Not surprisingly, then, Twitter has been the source of a couple of the major gaffes of Durant’s career. He once, excruciatingly, responded to a critic in the third person (“Kd can’t win a championship with those cats”) — thereby accidentally revealing that he was trying to defend himself, anonymously, from a fake account. (The Onion recently published an article called “Kevin Durant Spends All Day Feuding With Own Burner Account.”) More recently, Durant was caught up in a furor when Michael Rapaport, a professional loudmouth, exposed a series of inflammatory messages — including sexually explicit and homophobic language — that Durant had made to him, months earlier, as the two argued in the D.M.s. (The N.B.A. eventually fined Durant $50,000.)

“Anybody that’s crucifying me for some [expletive] that I said behind closed doors,” Durant told me, “I would definitely love to see y’all phones.”

I asked Durant if, just anthropologically, I could take a peek at his Twitter mentions.

He said no. But he described them for me. “It’s like: ‘u a bitch.’ ‘u soft.’ ‘u insecure.’ ‘i love u kd, can you respond?’” Basically, it’s a constant fire hose of praise and insults and cries for attention. I asked him if his brain exploded every time he opened the app.

“My brain doesn’t explode,” he said.

“How does it not explode?” I asked.

“Because I’m a very centered, balanced person,” he said. “I understand why these people are doing this. If I didn’t understand, then I probably would go crazy.”

What Durant understands, he explained, is that the people writing to him aren’t actually writing to him. Kevin Durant, to them, is just an abstraction, a guy on the TV, a figment of their imaginations. So what they are doing is projecting onto him the pain or hatred or longing that they actually feel about real things in their own lives. This is why he likes to write back. He wants to show them that he is an actual human, just like them, with his own fears and hatreds and longings. He wants to connect with them on that level. Even the angry ones, he believes, have good hearts. Hatred, he told me, is just another form of passion, and therefore a sign that you’re really alive.

“I can work with that,” he said. “I want to see what’s underneath.”

“And you can get there?” I asked.

“I know I can. People are naturally emotional when they talk to somebody they feel is on a higher pedestal than them. I’m trying to say: We equals at the end of the day. Once I bring ’em up to that, then they realize what they was doing was childish.”

Then Durant got biblical.

“Jesus used to do that,” he said. “He used to go to the worst places, and go find the people who hated him, absolutely hated him. Who denied him, never even thought about saying his name. He went to go holla at them and give them the truth. And once they heard the truth they souls changed, and they couldn’t deny it. So I try to take that approach.”

“In your mentions,” I said.

“In everything I do.”

2. More lessons about Jesus:

3.

Read this portrait of an intriguing character willing to risk comfort for authenticity. This article is especially relevant to Austinites, Texans, and anyone who envisions themselves as an artist. I’m a huge fan of Dave Hickey’s essays, especially his collection Air Guitar. Link to essay here.

4. Taking on authoritarian dictators since age 16— 🤯

5. Another example of a human doing what most humans can’t fathom; the slow-motion version makes me want to re-check some physics formulas for accuracy.

6. I read a book called Systems Thinking for Social Change by David Stroh. Here’s the mind-map I made—drag it to your desktop and enlarge it for further viewing clarity.

If you’re a subscriber, consider this MindMap part of your subscription. If you’re not a subscriber, here’s my Tip Jar 🍯 so you can flex those hot generosity muscles. Or: